Part three(i) of Grounding your Research –

How is this more than just my opinion?

Many artists read art theory—even dense academic papers at times—but do we notice the structures within these texts?

Understanding this is more urgent when we—artists as researchers—are producing a thesis ourselves.

In the case of philosophy and certain related theoretical disciplines, there are “structures”. Similar to the building blocks PQC, reviewed earlier, but more complex. These “structures” are writing tools/methodologies for philosophers.

This series focuses on those tools/methods used by Philosophers (and by extension, critical theorists), for grounding knowledge and building argument from that ground.

Philosophers, as we will see, innovate with logic structures as well as performative properties of the medium of writing itself. For philosophers, then, methodology is not about how to do experiments and how to interpret statistical results… their methodology is about how they think as expounded or performed by writing.

For philosophers, thinking is the method.

Think about that for a moment.

Philosophy is traditionally understood only through language/texts, so we mistake writing to be a philosophic method. In fact, writing is a medium that we progress through (it’s time-based (page 1, page 2, page 3) and also somewhat spatial (our eye can rove around a page noticing diagrams and headings and footnotes)). There are structures making use of these time and space properties of text—how different sentences are joined together to create logical progressions which philosophers use with the intention of representing movements of thought through writing.

Methods part 1 – Dialectics and immanent critique, origins and evolution

Transcendental critique (after Kant). (against which background, dialectics is often presented.)

A somewhat unpopular approach ever since Nietzsche killed god, but Kant is remembered as one of the last major figures in the western tradition of philosophy to try to ground knowledge in a priori concepts that are accessible to us. A priori concepts are independent certainties such as god or mathematics or tautologies. They are abstract, universal, unchanging, external to us and the world of senses, and underpin everything else.

Before Kant, rational metaphysical theories (after Plato, Descartes, Leibniz), following from deep skepticism towards the reliability of sense data, attempted to show that we do have access to how things are (by virtue of god/platonic heaven etc. which ensures it) for the purpose of grounding knowledge/dealing with their doubt. These ideas were in conflict with (proto-science) empiricist views (Locke, Hume etc.) who believed we only have access to how things appear through the senses (and moreover we should stop belly-gazing and get on with measuring things in the world).

Kant is particularly notable for reconciling these opposing ideas, he thought that our grasp of how things are, mediated through our senses is filtered, but nonetheless tethered to how things really are, so we can then proceed to build knowledge from external sensed reality, safely anchored to the seabed of how things actually are. This is a theory that says the external world as we perceive it, corresponds (transcendentally) to the true nature of things.

Diagramming out the above (you can speed up videos..)

How on earth could I put this to use in my thesis?

For the purpose of grounding your research, Kant’s transcendental argument is perhaps more useful as a note on your mental “map of methods” for the purely intellectual purpose of understanding the history of how other methods emerged. As noted in a Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article, Kant’s method has been largely diminished by later theorists.

The debunking of Kant may be more useful to your thesis than the method itself, because you can watch out for claims in your text that refer to a priori ideas, if you agree with subsequent philosophers that it’s logically problematic to prove the sturdy nature of the ground you are attempting to build on.

However, in one respect the anti-sceptical claims of Kant’s Transcendental Argument have a possible contemporary use. As the Standford article notes, the abiding utility of this theory comes from the standpoint of ethics.

Any argument beginning with an ethical standpoint that “an action is right because it is good”, is using some form of thinking about the independent nature of “good” which resides in platonic/spiritual/eternal belief.

If your thesis deals with “social good” via, for example, relational aesthetics, then at a deep embedded level of your thesis logic, you may already be leveraging ethical philosophical methods via Kant regarding the independent nature of “good”. Without the idea of good, we are in big trouble so it’s perhaps not a bad thing to be a little pluralistic with your application of Kant.

Dialectics/immanent critique (after Plato, Hegel, Fichte, Marx)

Notions of dialectics have appeared in various forms throughout the history of philosophy. First in the Socratic dialogue/Platonic form of dialectics, where the argument works to reconcile contradictory views through synthesis of more than one opinion. Contrast with “eristics”—trying to win the argument, at the expense of the truth.

Dialectics was reimagined by Hegel, after Kant, to be the substantive material of reality itself e.g.—Idea (the French Revolution), It’s negation (the Reign of Terror that followed), Synthesis of both (the constitutional state of free citizens). In Hegel, our perception of history is in fact a “dialectic impetus” of the world spirit (weltgeist) unfolding through time towards an eventual absolute Idea(—see video).

We should note that if we have abandoned the position of Kant mentioned above (that how we perceive things corresponds to how they truly are), then the dialectical method of asserting that your argument is more than just your opinion has already become quite fleeting and sparse. The research is grounded in a very modest way by dealing with only the observable contradictions internal to a topic and not attempting to impose external criticisms or making absolute claims.

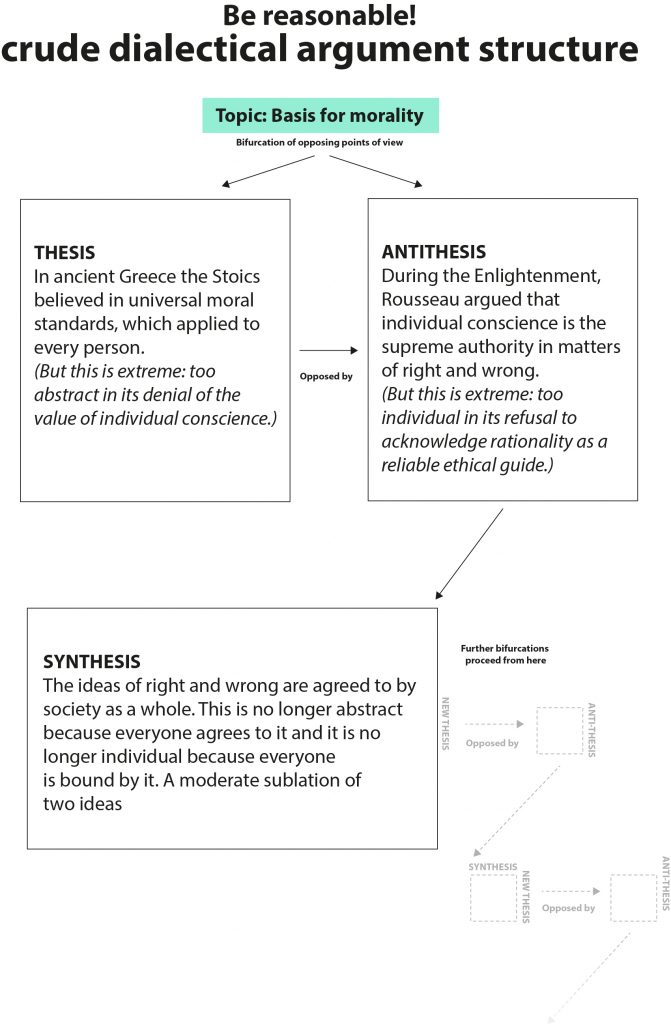

Later, Johann Gottlieb Fichte was responsible for propagating this now famous “thesis-antithesis-synthesis” framework of argumentation although it is still largely attributed to Hegel, erroneously in the view of many.

In a cruder form, dialectics as a writing pedagogy remains a hugely popular method throughout the twentieth and twenty first century so it’s likely you have already read many dialectically-informed texts even if you are not aware of the way the author is specifically using this method as a claim for how the argument is not merely opinion. There is an attempt to “be reasonable” in acknowledging other views, and finding ways to reconcile the contradictions.

In Hegel’s Science of Logic,

[T]he refutation must not come from the outside, that is it must not proceed from assumptions lying outside the system in question and which it does not accord with. The genuine refutation must penetrate the opponent’s stronghold and meet him on his own ground. No advantage is gained by attacking him somewhere else and meeting him where he is not.

Hegel, Werke, 6, 250, via Adorno, Against Epistemology: A Metacritique (Studies in Husserl and the Phenomenological Antinomies) translated by W. Domingo (Oxford, 1982)

When setting out with this method, not only is it bare-bones, it is also not apparent what kind of contradictions you might find within a topic, and each new topic requires you to really think and investigate without any simple pattern of investigation.

And yet, paradoxically, it is one of the most patterned-out philosophical methods in the canon, partly because Marx took it and made it material.

“From the experience of reading abstract philosophical texts, we all know the relief one feels when the argument is interrupted by what we call a ‘concrete’ example. Yet at that very moment, when we think at last that we understand, we are further from comprehension than ever.”

–The Rhetoric of Romanticism, p276, Paul de Man

Thanks, de Man, but this philestean loves an example:

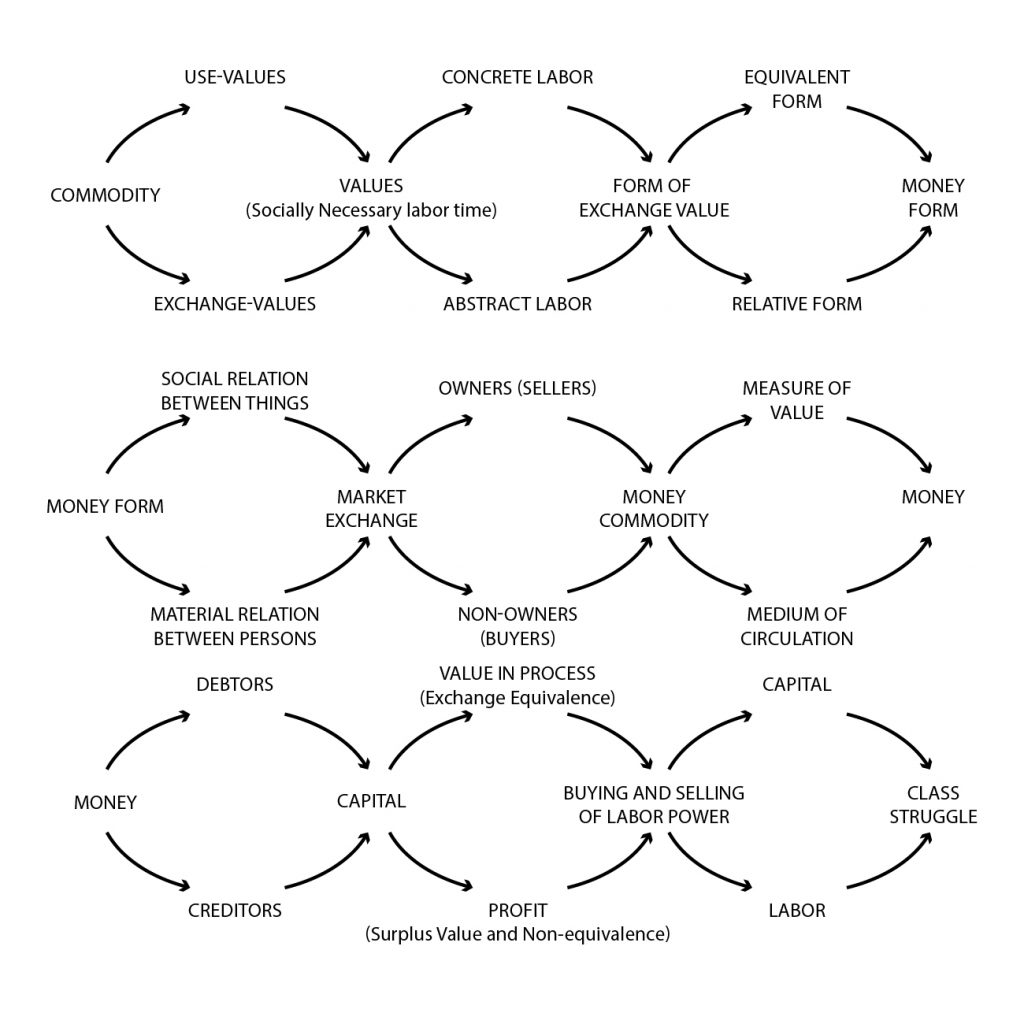

Let’s turn to Marx where the dialectic/proto-immanent critique structure is clear. Marx does not seek to use experiments and analysis of statistics to prove capitalism exists in the world, rather, in Kapital, the argument takes a generally understood concept – capitalism, locates an internal struggle – proletariat vs bourgeoisie and discovers rather than contradicting each other, these opposing forces are necessary for the definition of the other. Without a proletariat there cannot be a bourgeoisie, without a bourgeoisie there cannot be a proletariat, therein synthesising the contradiction which is capitalism.

In the above example we can see now, concretely, the unfaltering structure of the logic in Marx. A topic splits apart into contradictions as a position encounters its “other”, and the subsequent “sublation” (think: coffee grains and water ascending to the bialetti pot as coffee)—each resolving into a unity.

Following the dialectics of Plato, Hegel/Fichte, Marx, the related process of Immanent Critique, refined by Walter Benjamin / the Frankfurt School / Adorno etc, is to radically restrict the discussion in an argument to the dynamics present within a certain system or topic. Looking only at its internal (immanent) contradictions in order to reveal the nature of the topic and avoiding outward leaps.

Wrapping up

We should observe how this framework for writing is at a higher level than PQC—here we are specifically setting out to find contradictions and use them to discover a greater sense of truth.

First seek out someone with whom to argue; one there-by gradually finds one’s way into the question at issue, and the rest will follow of itself.

G.E. Lessing quoted in A History of German Literary Criticism, 1730-1980 p57, via Finlayson (2014)

PQC on its own is a building block with no inherent trajectory. It could be used eristically (only presenting one-sided arguments in order to win, regardless of truth) or apologetic (defending arguments that are already known to be true) but dialectics is purposeful in attempting to understand how sublation of contradictions gives us greater access to the truth—which is the stated goal.

Dialectical structures are seductive, they provide a rough and ready answer to “how is this more than my opinion”—after all, you synthesised at least two opinions, right? As long as they weren’t intentional straw men, you’ve wrestled with accommodating contradictory forces within a topic. Dialectics as a method is neutral, it can be done well and badly like any other.

In future posts, I will look at phenomenological methods, networks and tentacular thinking, and performative methods.

Further resources from Hegel to Immanent Critique

(i) Finlayson, J. G. (2014) Hegel, Adorno and the origins of immanent criticism. British Journal for the History of Philosophy

(ii) Late Marxism: Adorno, Or, The Persistence of the Dialectic by Fredric Jameson

Leave a comment